What the Fundamentals Say About Future Oil Prices

A lot of observers are looking for lower oil prices in the short term.

They cite:

My thesis is based in part on the hoarding mindset that now dominates the oil market and is hardly ever discussed. Exporters (read OPEC, particularly KSA, UAE, Kuwait, and Venezuela) are now addicted to high and rising oil prices. Their ever increasing cash flows from oil have led to their making huge future capital commitments; they are not willing to see falling oil prices endanger those commitments. They also know that due to tight global supplies relatively minor production cuts are sufficient to raise prices. Finally they now believe that oil in the out years will only get more expensive. Thus near term production cuts will also be rewarded because the oil not sold now can be sold later for more money. In summary, exporters today have their hands on a hair-trigger for raising the oil price and they will not hesitate to pull it if the price falls much below $85. I summarize this series of attitudes on the part of oil exporters as the “hoarding mindset.”

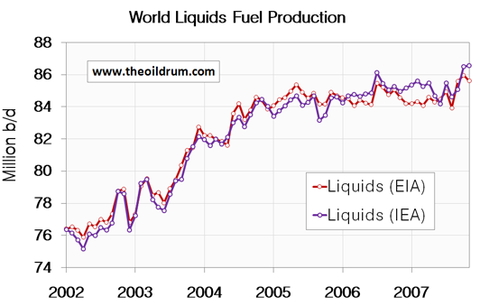

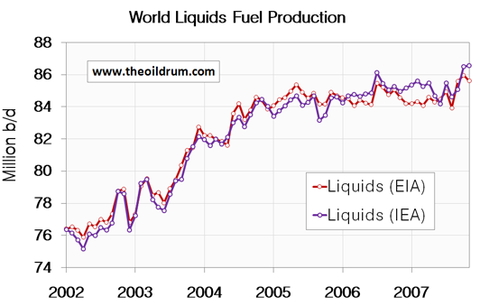

Meanwhile global oil production is now at an historically high level but still does not seem to be able to satisfy demand. The Saudis and the Iraqis have both managed to increase production by roughly 500,000 b/d helping to cause the 85 mb/d global production plateau that has existed for nearly two years to be eclipsed during the past few months; production now seems to be running in excess of 87 mb/d as shown in this chart:

Figure 1 - World Liquids Fuel Production January 2002 - November 2007

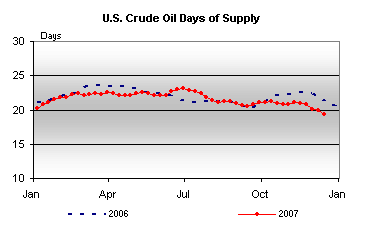

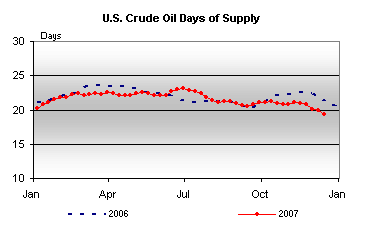

Yet the price of oil refuses to sink. Each time oil goes into the high $80s it seems to bounce right back in the face of tight inventories. U.S. crude oil inventories keep sinking – they are now the lowest in nearly three years. This is a chart that indicates the tightness of U.S. oil supplies measured in days of inventory:

The only way that global supply can be rising and still be tight is that demand must be rising even faster. Recent front page articles in the Times and the Journal have highlighted rapid demand growth among oil producing countries like Mexico and Saudi Arabia. Those articles describe only a part of the total picture. In fact all countries that are exporting either oil or goods in great quantity, such as China and India, are ramping up their rate of oil consumption by 5% - 7% a year. If such countries consume 30% of all oil globally, and assuming consumption in all other countries is flat, their consumption growth rate translates to a global growth rate of about 1.5 - 2%, which, in fact, is about what the rate of increase in oil consumption has been running.

The International Energy Agency recently increased their projection for new oil demand in 2008 from 1.9 mb/d to 2.1 mb/d, a global growth rate of about 2.5%. The IEA tends to be pessimistic about the adequacy of oil supply. OPEC, on the other hand, predicts demand growth of just 1.3 mb/d, which seems designed to justify their producing less oil than the IEA would like. See discussion above re: hoarding.

What About the Energy Bill?

The new Energy Bill is a bit mysterious in some respects. For example, it is not clear yet – at least to me – how the biofuel mandates will work. The bill calls for enormous increases in biofuel production and use. What if a target is not hit? Does someone go to jail? Infrastructure and feedstock bottlenecks on ethanol may limit supply in the near term. Ultimately biofuel use will depend on the emergence of new technologies to produce ethanol cost effectively and to scale. I continue to believe that biodiesel has a better chance to be the big winner, as discussed here. In sum, the real impact of the Energy Bill’s bio-fuel mandates remains to be seen.

New CAFÉ standard will probably have a more predictable outcome. Individual car companies would probably pay fines if their CAFÉ standard is not met. I suspect the standards will be taken seriously and will give further impetus to the current efforts by car makers to offer far more efficient vehicles to the public. Whether they buy them or not is a different matter. We’ll need consistently higher oil prices to spur demand. Even with that, the new standards do not hit until 2011, limiting the impact of this bill during the next five years, which is the relevant investment time frame. All that said, though, over the long term the new standards will tend to make the U.S./Canadian fleet much more efficient; it is certainly a good thing.

In sum, the impacts of the new Energy Bill will occur over a long time and they will phase in very slowly. How will it impact oil prices? Well, if the U.S. can reduce oil consumption by 1% a year while still increasing the fleet size that would save about 200,000 barrels per day per year. Given that demand from developing economies is growing at 1.5 – 2.0 mb/d per year, such a North American reduction would be helpful. But in no way would it be a game changer in terms of the global oil price, particularly during the next five years.

On the other hand, some commentators will interpret the biodiesel and ethanol “mandates” as accomplished fact and argue that they will thus reduce U.S. gasoline consumption by significant amounts. So the bill could help manage public expectations in the direction of reducing their perception of the urgency of the Peak Oil problem. Keeping expectations low could dampen oil price speculation, perhaps tending to reduce futures prices. Of course, that might then have an impact on OPEC production, which takes us right back to the earlier discussion of hoarding.

Old Field Decline: A New Data Point

Then there is the never-reported and always-critical matter of the decline in production from old fields. An interesting nugget of news was contained in the Wall St. Journal story referenced above. Buried in the middle is a report that the rate of decline in Saudi oil production from existing fields is 6.6% a year. That is a large number. Chris Skrebowski estimates that global decline is running 3.3% per year. A 6.6% KSA decline rate would mean that the Saudi’s need to add abut 600,000 barrels a year in new production just to produce at the same rate as the prior year. That does not bode well for the basic assumption embodied in the projections of all Wall Street analysts that KSA is the global swing producer that can (and, they believe, will) save the world from higher prices.

What Fundamental Trends Are Saying About Future Oil Prices

While anything can happen in the short term, we should be able to make reasonable predictions of long term oil prices because, by definition, trends tend to last a long time. Here are the trends in oil that I believe to be sustainable:

1. The natural rate of decline in old fields will grow slowly every year.

2. Enhanced Oil Recovery [EOR] methods for improving the recovery of oil from old fields will continue to improve, thus tending to reduce the actual rate of declining production from the old fields to which EOR is applied. But the impact of EOR is already part of the existing 3.3% global decline rate. Improved EOR technologies will not reduce the global decline rate but will keep the rate from rising faster than it would otherwise.

3. Once a given field to which EOR has been applied begins to decline, its rate of decline will be much faster than that of a field to which EOR was not applied since EOR leaves less oil in the ground to be recovered during the extended final life of the field. Cantarell’s 15% decline rate is a paradigm example. At any point in time, this phenomenon could have a substantial impact on global oil supply. If Ghawar were to start to resemble Cantarell, for example, one could see a doubling of the oil price in short order.

4. Rapid growth in oil demand from countries that have high exports of oil or other goods will continue for decades to come. Therefore, global demand growth of roughly 1.5 – 2 mb/d from developing economies will continue for the foreseeable future.

5. Most future new production will come from either deep offshore or from alternative sources such as oil sands. Such resources require long time frames to develop and very high costs to recover. Therefore, new source oil is inherently limited in the rate at which it can be brought on stream and will require increasing marginal oil prices to be feasible.

The logical conclusion from these trends, I think, is that oil production beyond 2009 is likely to fall well short of the sum of growing demand and increasing declines in old fields. They lend credibility to the statistical analysis done by Chris Skrebowski that indicates we will see the benefits of numerous new, primarily land-based projects scheduled to come on stream in 2008 and 2009, after which supplies will become significantly tighter, falling off a cliff by 2014.

This is not to say that there are not potential bright spots such as Libya, Iraq, Nigeria, and Angola. It is possible that oil supply could surprise on the upside. But what I think is distinctly not a bright spot during the next five years are hopes for significant production increases from Canadian oil sands, Venezuelan oil sands, Colorado oil shale, the Gulf of Mexico Jack discovery, or the recent Brazilian find. The latter two are potentially gigantic finds, but the time needed to recover the oil and the costs for recovering it are similarly gigantic.

Fearless Prediction

Considering all of the above, my five year forecast for the oil price range is:

2008: $80 - $140

2009: $105 - $195

2010: $150 - $250

2011: $175 - $325

2012: $275 - $500

They cite:

- a looming recession

- 2003 - 2007 higher prices resulting in demand reductions and supply increases

- the end of dollar weakness

- the end of Chinese preparations for the 2008 Olympics

- reduced geopolitical tensions, especially regarding Iran

My thesis is based in part on the hoarding mindset that now dominates the oil market and is hardly ever discussed. Exporters (read OPEC, particularly KSA, UAE, Kuwait, and Venezuela) are now addicted to high and rising oil prices. Their ever increasing cash flows from oil have led to their making huge future capital commitments; they are not willing to see falling oil prices endanger those commitments. They also know that due to tight global supplies relatively minor production cuts are sufficient to raise prices. Finally they now believe that oil in the out years will only get more expensive. Thus near term production cuts will also be rewarded because the oil not sold now can be sold later for more money. In summary, exporters today have their hands on a hair-trigger for raising the oil price and they will not hesitate to pull it if the price falls much below $85. I summarize this series of attitudes on the part of oil exporters as the “hoarding mindset.”

Meanwhile global oil production is now at an historically high level but still does not seem to be able to satisfy demand. The Saudis and the Iraqis have both managed to increase production by roughly 500,000 b/d helping to cause the 85 mb/d global production plateau that has existed for nearly two years to be eclipsed during the past few months; production now seems to be running in excess of 87 mb/d as shown in this chart:

Figure 1 - World Liquids Fuel Production January 2002 - November 2007

Yet the price of oil refuses to sink. Each time oil goes into the high $80s it seems to bounce right back in the face of tight inventories. U.S. crude oil inventories keep sinking – they are now the lowest in nearly three years. This is a chart that indicates the tightness of U.S. oil supplies measured in days of inventory:

The only way that global supply can be rising and still be tight is that demand must be rising even faster. Recent front page articles in the Times and the Journal have highlighted rapid demand growth among oil producing countries like Mexico and Saudi Arabia. Those articles describe only a part of the total picture. In fact all countries that are exporting either oil or goods in great quantity, such as China and India, are ramping up their rate of oil consumption by 5% - 7% a year. If such countries consume 30% of all oil globally, and assuming consumption in all other countries is flat, their consumption growth rate translates to a global growth rate of about 1.5 - 2%, which, in fact, is about what the rate of increase in oil consumption has been running.

The International Energy Agency recently increased their projection for new oil demand in 2008 from 1.9 mb/d to 2.1 mb/d, a global growth rate of about 2.5%. The IEA tends to be pessimistic about the adequacy of oil supply. OPEC, on the other hand, predicts demand growth of just 1.3 mb/d, which seems designed to justify their producing less oil than the IEA would like. See discussion above re: hoarding.

What About the Energy Bill?

The new Energy Bill is a bit mysterious in some respects. For example, it is not clear yet – at least to me – how the biofuel mandates will work. The bill calls for enormous increases in biofuel production and use. What if a target is not hit? Does someone go to jail? Infrastructure and feedstock bottlenecks on ethanol may limit supply in the near term. Ultimately biofuel use will depend on the emergence of new technologies to produce ethanol cost effectively and to scale. I continue to believe that biodiesel has a better chance to be the big winner, as discussed here. In sum, the real impact of the Energy Bill’s bio-fuel mandates remains to be seen.

New CAFÉ standard will probably have a more predictable outcome. Individual car companies would probably pay fines if their CAFÉ standard is not met. I suspect the standards will be taken seriously and will give further impetus to the current efforts by car makers to offer far more efficient vehicles to the public. Whether they buy them or not is a different matter. We’ll need consistently higher oil prices to spur demand. Even with that, the new standards do not hit until 2011, limiting the impact of this bill during the next five years, which is the relevant investment time frame. All that said, though, over the long term the new standards will tend to make the U.S./Canadian fleet much more efficient; it is certainly a good thing.

In sum, the impacts of the new Energy Bill will occur over a long time and they will phase in very slowly. How will it impact oil prices? Well, if the U.S. can reduce oil consumption by 1% a year while still increasing the fleet size that would save about 200,000 barrels per day per year. Given that demand from developing economies is growing at 1.5 – 2.0 mb/d per year, such a North American reduction would be helpful. But in no way would it be a game changer in terms of the global oil price, particularly during the next five years.

On the other hand, some commentators will interpret the biodiesel and ethanol “mandates” as accomplished fact and argue that they will thus reduce U.S. gasoline consumption by significant amounts. So the bill could help manage public expectations in the direction of reducing their perception of the urgency of the Peak Oil problem. Keeping expectations low could dampen oil price speculation, perhaps tending to reduce futures prices. Of course, that might then have an impact on OPEC production, which takes us right back to the earlier discussion of hoarding.

Old Field Decline: A New Data Point

Then there is the never-reported and always-critical matter of the decline in production from old fields. An interesting nugget of news was contained in the Wall St. Journal story referenced above. Buried in the middle is a report that the rate of decline in Saudi oil production from existing fields is 6.6% a year. That is a large number. Chris Skrebowski estimates that global decline is running 3.3% per year. A 6.6% KSA decline rate would mean that the Saudi’s need to add abut 600,000 barrels a year in new production just to produce at the same rate as the prior year. That does not bode well for the basic assumption embodied in the projections of all Wall Street analysts that KSA is the global swing producer that can (and, they believe, will) save the world from higher prices.

What Fundamental Trends Are Saying About Future Oil Prices

While anything can happen in the short term, we should be able to make reasonable predictions of long term oil prices because, by definition, trends tend to last a long time. Here are the trends in oil that I believe to be sustainable:

1. The natural rate of decline in old fields will grow slowly every year.

2. Enhanced Oil Recovery [EOR] methods for improving the recovery of oil from old fields will continue to improve, thus tending to reduce the actual rate of declining production from the old fields to which EOR is applied. But the impact of EOR is already part of the existing 3.3% global decline rate. Improved EOR technologies will not reduce the global decline rate but will keep the rate from rising faster than it would otherwise.

3. Once a given field to which EOR has been applied begins to decline, its rate of decline will be much faster than that of a field to which EOR was not applied since EOR leaves less oil in the ground to be recovered during the extended final life of the field. Cantarell’s 15% decline rate is a paradigm example. At any point in time, this phenomenon could have a substantial impact on global oil supply. If Ghawar were to start to resemble Cantarell, for example, one could see a doubling of the oil price in short order.

4. Rapid growth in oil demand from countries that have high exports of oil or other goods will continue for decades to come. Therefore, global demand growth of roughly 1.5 – 2 mb/d from developing economies will continue for the foreseeable future.

5. Most future new production will come from either deep offshore or from alternative sources such as oil sands. Such resources require long time frames to develop and very high costs to recover. Therefore, new source oil is inherently limited in the rate at which it can be brought on stream and will require increasing marginal oil prices to be feasible.

The logical conclusion from these trends, I think, is that oil production beyond 2009 is likely to fall well short of the sum of growing demand and increasing declines in old fields. They lend credibility to the statistical analysis done by Chris Skrebowski that indicates we will see the benefits of numerous new, primarily land-based projects scheduled to come on stream in 2008 and 2009, after which supplies will become significantly tighter, falling off a cliff by 2014.

This is not to say that there are not potential bright spots such as Libya, Iraq, Nigeria, and Angola. It is possible that oil supply could surprise on the upside. But what I think is distinctly not a bright spot during the next five years are hopes for significant production increases from Canadian oil sands, Venezuelan oil sands, Colorado oil shale, the Gulf of Mexico Jack discovery, or the recent Brazilian find. The latter two are potentially gigantic finds, but the time needed to recover the oil and the costs for recovering it are similarly gigantic.

Fearless Prediction

Considering all of the above, my five year forecast for the oil price range is:

2008: $80 - $140

2009: $105 - $195

2010: $150 - $250

2011: $175 - $325

2012: $275 - $500

No comments:

Post a Comment